Even if you’re not a researcher, you’ve probably encountered frustrating user interfaces (UI) and had a terrible user experience (UX). Maybe it’s a new phone that you struggled to find settings on, or an application where nothing was where you expected it to be. NCSA’s UI/UX experts know these frustrations well, and their job is to work with research teams that use and develop custom applications for their projects to make those solutions as easy to use as possible.

Building an Amazing Design Team

Lisa Gatzke leads NCSA’s UIX design team and has decades of experience perfecting the user experience. She’s been working on designing user interfaces for 25 years, and she even worked as a student at NCSA while pursuing a graphic design degree. She has experience working with industry, including a Fortune 500 company, as well as working with research institutions like NCSA. All this knowledge has made her the perfect mentor for her team.

Kate Arneson and Leigh Fu are members of the Center’s UIX team, along with Emma Grisanzio and Jackson Vaughan. Arneson and Fu recently presented their paper, Toward More Usable, Reproducible, and Sustainable Scientific Software: The Impact of User-Centered Design in Research Software Development, at the annual Platform for Advanced Scientific Computing (PASC) conference. Their paper was so impressive that PASC selected Arneson and Lijang for the Best Paper Award, which came with a spot in the PASC Keynote speaker schedule.

While Gatzke gives all the credit for the paper to Arneson and Lijang, both UIX team members are quick to point out that Gatzke played a significant role in their achievements.

“Most of the design philosophies at the beginning of the paper come from Lisa,” said Fu. “We gave a presentation together at the US-RSE conference last year, and there we watched Lisa educate people about what UI and UX are. We really wanted to take what she defined and put it into the paper, so in that way, she’s as much an author as we are.”

“Even if we’re a lead on a project like the ones we presented on at PASC, Lisa is always there for consultation,” added Arneson. “Depending on what we need, she’ll meet with us in team meetings, or one-on-ones, and she’s great at giving feedback and asking questions because she’s built up so much knowledge and experience over the years.”

The highly collaborative team leverages interdisciplinary backgrounds to bring innovative ideas and perspectives to every project. When Arneson was an undergrad studying math and studio art, she wasn’t aware that a formal UI/UX career existed. In her first professional roles, she primarily worked on math- and statistics-oriented research teams, but when she met her first UI/UX collaborators, everything changed.

“On several projects, we had UX designers on our broader team,” she said. “I thought what they were doing looked really interesting. It combined a lot of the creative and analytical aspects that I enjoyed in my undergraduate studies, and, at the time, I missed having more of that creativity in my work. So I completed a certificate program in UX design, connected with NCSA, and have been working here now for a little over two years.”

Fu comes from a different discipline – she studied industrial design for both her undergraduate and graduate degrees. She had much more experience designing things you can hold.

“For industrial design work, I primarily focused on designing the physical products,” said Fu. “I used CAD software to create physical products. But what truly shaped my design mindset was being introduced to human-centered design and design research methodologies during school. These experiences taught me that deeply understanding user needs and practicing empathy is the driving force of design and essential for building successful, user-centered products. During internships at startup companies, I also took on software interface design work, creating digital interfaces to complement physical products. The skill set for both is very similar. Both require thoughtful design research and intuitive problem-solving. No matter the medium, I want the user experience to feel effortless and enjoyable.”

Elements that Make Great UI/UX Design

A UI/UX team was very likely hired to help turn a prototype into something not only functional, but usable and intuitive for many of the applications you’ve used, from powerful desktop software like Photoshop to web applications you use to check your bank account. Going from an idea to an implementation that’s easy to use requires a lot of work, and in the world of academic research, UI/UX designers are quickly becoming a hot commodity. That’s partly because research is becoming more and more complex, often with teams scattered across the country, or even the world.

Research increasingly uses high-performance computing (HPC) to crunch data or perform complicated simulations. Interfacing with these powerful machines can be confusing, especially when many researchers have never worked with cyberinfrastructure (CI) before. A supercomputer’s UNIX interface is a very different beast from your typical PC or MAC, which comes with user-friendly graphical user interfaces (GUIs) rather than the somewhat intimidating command line.

Researchers should be able to focus on their work, rather than learning or thinking about how to navigate a complex custom application, and that’s where Gatzke’s team comes in.

“I was watching a video interview with Charles Eames – Charles and Ray Eames were famous industrial designers,” explained Gatzke. “In the interview, they used the term ‘design thinking,’ which feels like it presumes that design has some sort of intrinsic virtue that affects the way you think about the things you know. So, what is design? In essence, design is really just the art of solving problems. It’s a way of thinking where you’re working toward the goal of creating a solution in a way that makes it better for the person who will use the solution.”

As Gatzke explains, in order to design a solution that is intuitive, you have to know the person who’s going to use the solution first. “This applies to all design,” Gatzke said. “It applies to designing a poster, designing a book, designing a computer interface – you have to know your user in all these instances, and really design the thing to answer the questions of the user. For user interface design, we’re arranging elements in space and time. So we’re thinking about what needs to be interactive, where to communicate, what kinds of patterns we need to employ that people intuitively understand, and then how that happens through time as somebody’s using a workflow within a software application.”

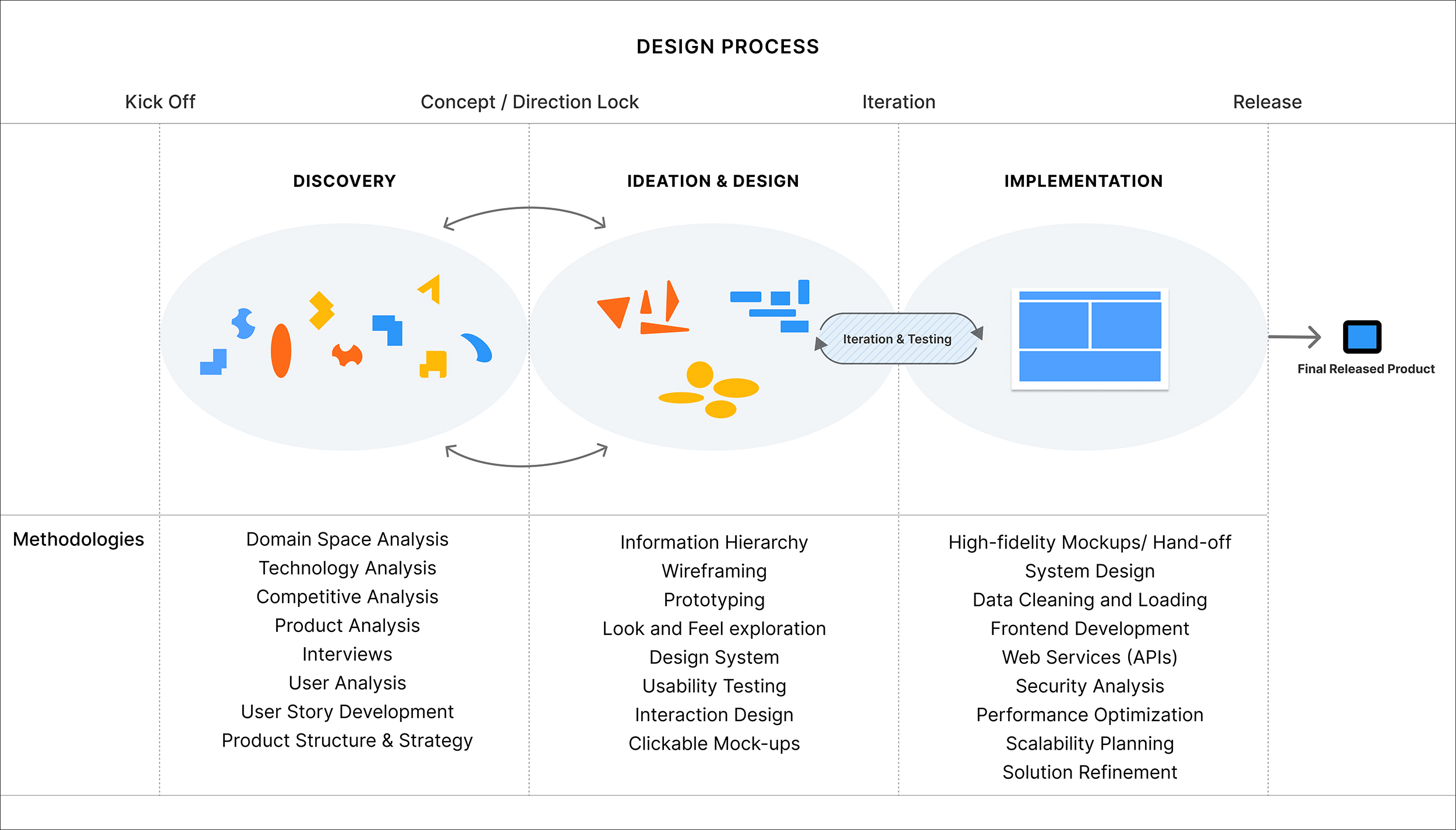

This means that a lot of time is spent talking to the researchers who will eventually use the application before anyone starts designing anything. This part, in particular, can take researchers by surprise. Gatzke’s team is embedded in the research software development team, and they interact closely with the researchers, particularly during these early stages.

“It’s sometimes hard to communicate to stakeholders how important the very early stage of the design process is,” explains Gatzke. “All of our research, interviews and questions, getting to understand the users, all that stuff that happens before we draw anything on the screen. That means that, as a service, we can help researchers who may not be sure what they want exactly. We can help them conceptualize what they need in an application. It’s a very important part of the services we provide to our collaborators.”

Once the team has all the background information to start the design, they begin creating wireframes and mock-ups so that the developers they work with can begin building the application – but it’s not the last time they’ll interact with the researchers before the product is finished. UI/UX work requires a lot of testing to get it just right. Arneson and Fu explained this aspect of their work using the case studies in their paper as an example.

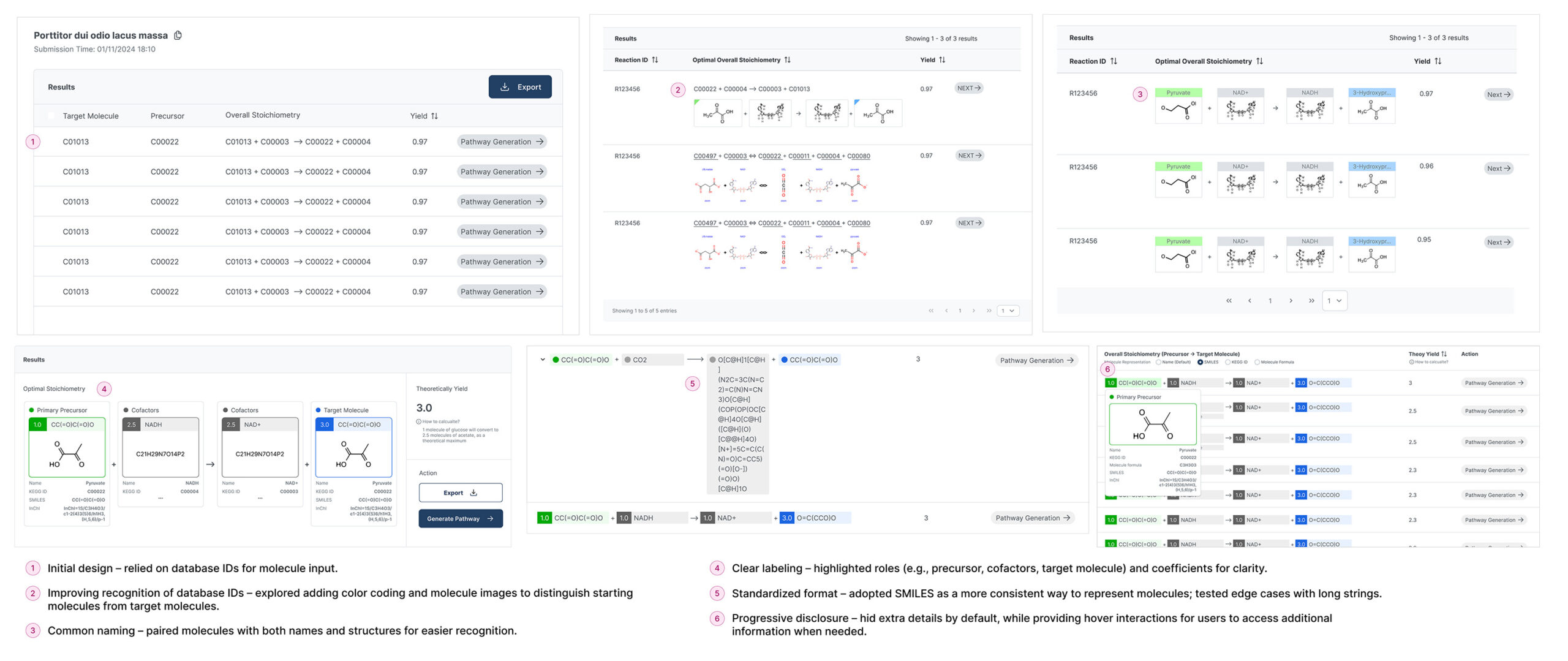

While working on novoStoic, a custom chemistry software for retrosynthesis pathway design, researchers brought the team an early experiment prototype. In this version, users had to input molecule IDs from a specific database. However, as Arneson and Fu got into the project, they realized that the molecule IDs were not consistent – different databases often assigned different identifiers to the same molecule, and researchers varied in how familiar they were with those databases.

“If the tool was to be adopted by a broader community, the input process needed to be intuitive and accessible,” said Fu. “This raised the question: How might we present this data in a way that a broader audience can easily understand, while keeping the workflow seamless within the tool?”

Once Arneson and Fu discovered the problem, they then decided to create a new way to identify the unique molecules that would be standardized for the shared application.

“We worked together with our domain expert, David Bianchi, ran some interviews with the potential users to understand their pathway design workflows and tried to identify a more suitable format for input and recognition,” said Fu. “That’s where we start to integrate the SMILES strings, which is a more standardized way for representing molecules.”

This iteration of their design had to be tweaked yet again because Arenson and Fu discovered that the researchers had different habits for inputting and recognizing molecules. So they adapted the input once more. The team then introduced a more flexible input method, including a molecule-drawing modal, so that researchers from different backgrounds could interact with and use the tool more intuitively.

Such rapid iteration and prototyping are common in the UI/UX design and testing phases. The back-and-forth between the researchers, UI/UX team and end users is an essential part of the process, and with each iteration, the interface becomes more and more usable by the audience it’s designed for.

“This discovery phase is central to the broader design thinking process and to our own process at NCSA,” said Arneson. “All the information that we uncover through doing user sessions, design iteration and usability testing is part of a circular flow where we talk to users, find out what they need, try out a solution, get their feedback, then iterate as needed and start all over again. The design thinking process is to change and iterate over time, and in doing so, you discover so many improvements along the way. We wouldn’t have known to make many of the necessary improvements without talking to users and actively working to understand their perspectives.”

More Than a Better User Experience

Good UI/UX design does far more than make using a research application easier or more pleasing to use – it also makes for better science. It’s not uncommon for large research projects to cycle members in and out of the team. New team members will be expected to pick up where others left off, and the knowledge between team members can vary greatly. Seasoned researchers will be on teams with student researchers, and they’ll all be tasked with using applications like those that Arneson and Fu helped to create.

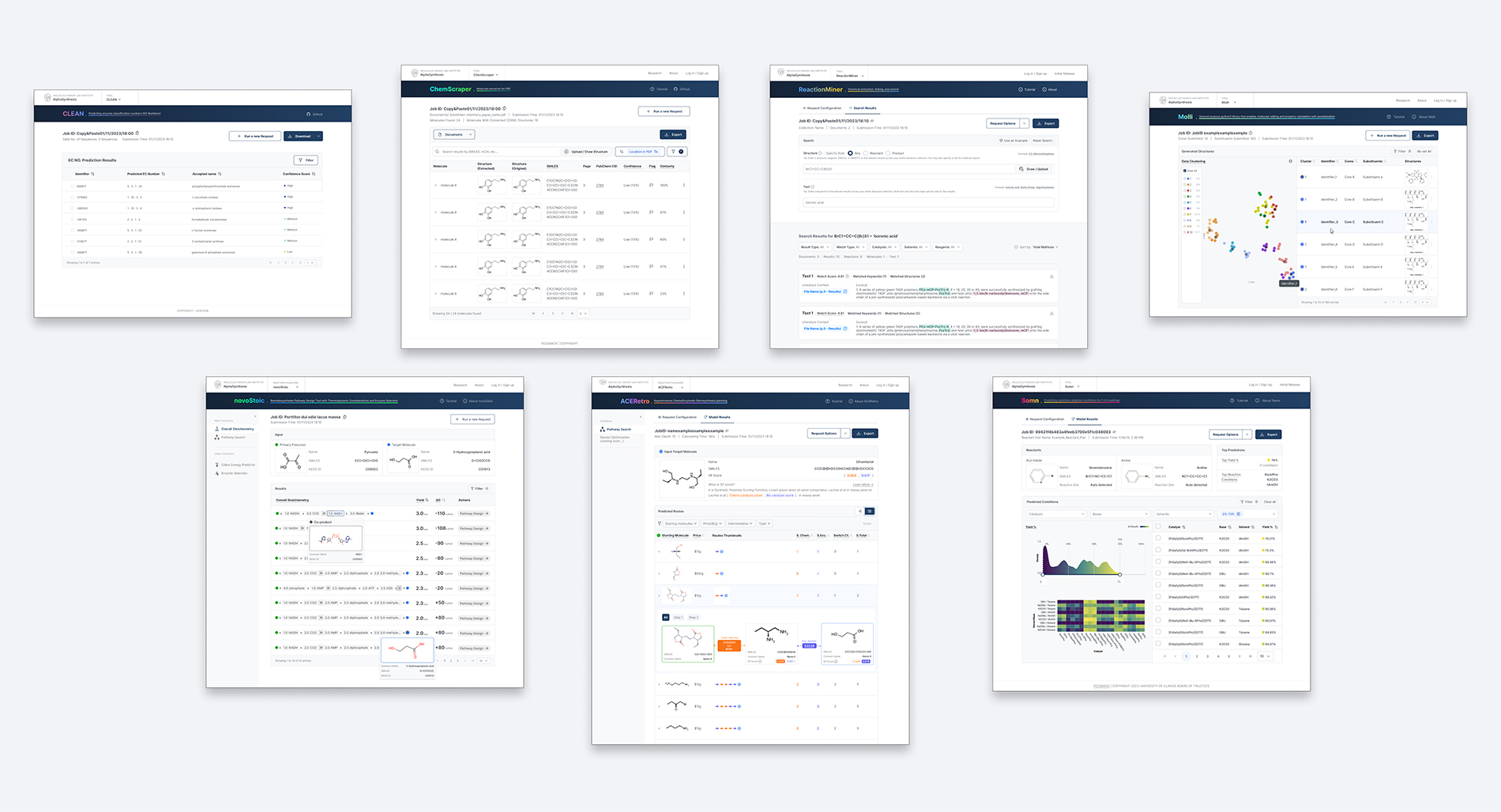

Everything from using a consistent hierarchy in menus to creating an interface with high memorability is part of the work. Gatzke’s philosophy is heavily influenced by Jakob Nielsen, a highly regarded expert in usability. Even something as simple as memorability is important to the team’s work – after all, researchers may have multiple projects they’re working on, and having an interface they can easily recall means less time getting back up to speed.

“Memorability is often overlooked, but we feel it’s a really important aspect of usability,” said Fu, “especially in scientific software. Across the nine or ten tools we have published or are about to publish, we focus heavily on consistency, both in user flow and in the content layout. For example, we make sure that core functions remain visible so users don’t have to dig through hidden menus, while advanced features are tucked away through progressive disclosure to keep common tasks clear and accessible. By maintaining predictable patterns in how users navigate input, results and actions, we help users to quickly orient themselves, even if they haven’t used a particular tool in a while. And by doing this, we’re also hoping to reduce the learning curve across the entire suite.”

By creating consistent, transparent, and user-friendly tools, we empower researchers to focus on their scientific goals while ensuring their processes and results are robustly reproducible.

–Katherine Arneson, et al., NCSA

Gatzke’s UI/UX team makes it easier for researchers to focus on their research instead of learning or operating the application. Easy-to-use tools mean fewer errors are introduced while inputting data, and that researchers of varying technical backgrounds have a similar experience. These are important elements when it comes to reproducible science. Sound science requires that the results can be reproduced – creating an interface that is highly intuitive means user error shouldn’t affect reproducible results.

Everything the team puts into the design is open source, which means that the work they do also contributes to sustainable output. Sustainability in application design means that the work holds up over time and can be used for other purposes going forward, rather than having a similar research team start from scratch.

“We knew we were on the right track when we got an email out of the blue from a researcher in Europe,” said Arenson. “That’s what happened with one of the MMLI projects. They were trying out the tool, and they found a bug. Of course, then the research team and our development team got on it and were able to address the issue. But more generally, this is an exciting example of open source creating more opportunities for global sustainability: one, we didn’t know that we had users in Europe, and two, the more people who use the tools and have the opportunity to provide feedback, the better the product becomes over time. When anyone can use the app like this, they widen our base of users and create new opportunities for us to keep the software useful and relevant for longer. It allows us to continue to improve and learn with an entirely new set of users, hopefully making the tool even more valuable for those who use it in the future.”

Gatzke sees the paper’s recognition at PASC as a sign that more researchers are beginning to see the value in including UI/UX developers in their projects.

“The research community does seem to have a growing interest in incorporating practices like these in software development,” she said. “But I think it’s important to note that NCSA has a lot of unique support for this already, and continues to value what our team has to offer, which is really awesome. The Center as a whole has this interdisciplinary nature, and our work is a part of that. That’s not just reflected in what we do, but in the makeup of our team in terms of our backgrounds. That NCSA has this service and researchers can make use of what our group specifically can offer is really special, too.”

ABOUT NCSA

The National Center for Supercomputing Applications at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign provides supercomputing, expertise and advanced digital resources for the nation’s science enterprise. At NCSA, University of Illinois faculty, staff, students and collaborators from around the globe use innovative resources to address research challenges for the benefit of science and society. NCSA has been assisting many of the world’s industry giants for over 35 years by bringing industry, researchers and students together to solve grand challenges at rapid speed and scale.